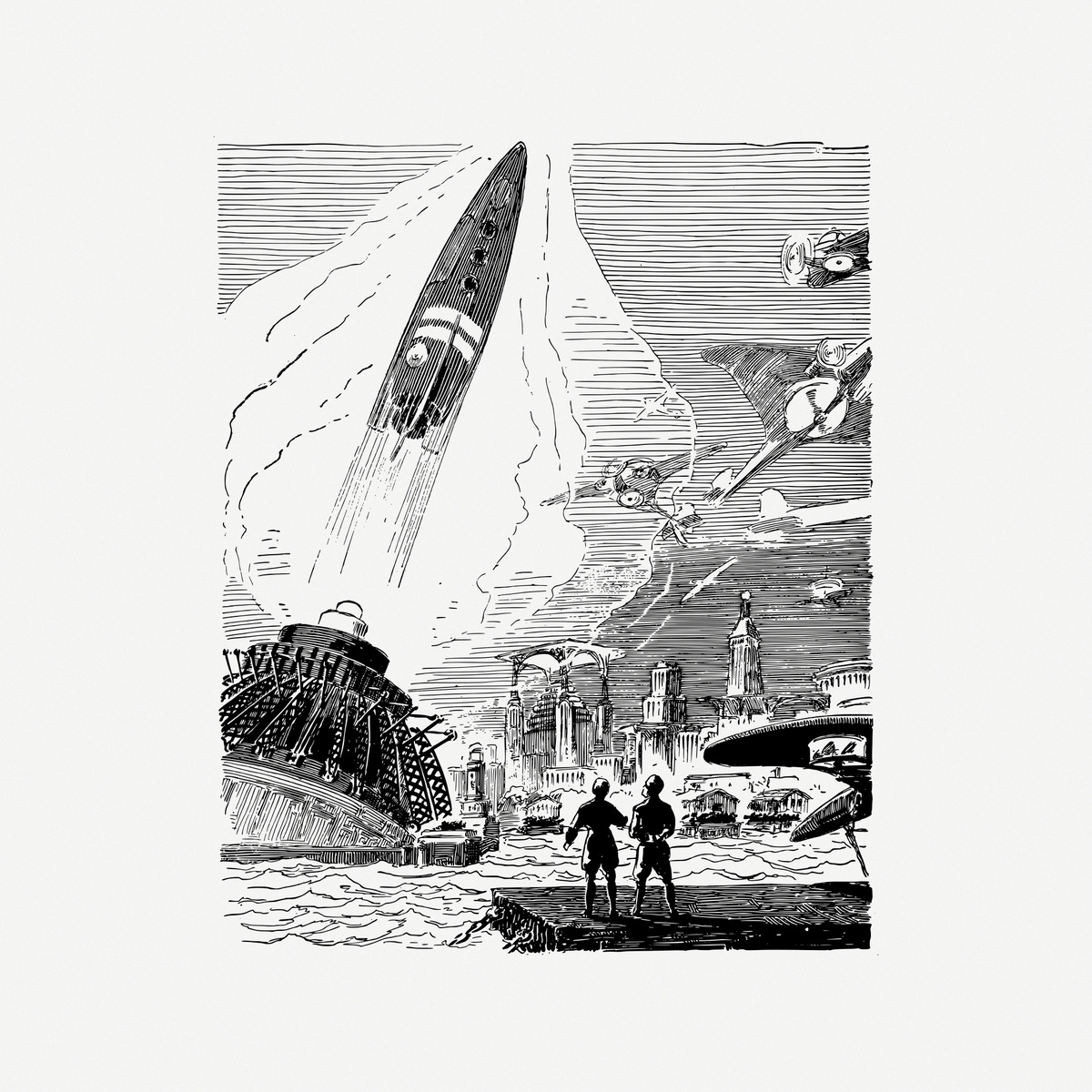

Take a moment to imagine a city of the future1. There are all sorts of futuristic cities we can imagine, but In this particular city, there is no such thing as the web2.

There are a few ways this could have happened. Maybe the city was wrapped in a giant Faraday shield, a measure of last resort applied by architects who had no other recourse. Maybe there are sophisticated firewalls that separate the internal networks from the global web, a digital shield against the informational wasteland beyond. Perhaps the web simply doesn't exist at all.

But why would we want to imagine this future city?

I.

Let's talk about the web.

Parts of the web are pretty great. A lot of the web is interesting and weird and thought-provoking. There are all kinds of fascinating art, communities, and people on the web, and those people make good, thoughtful, and weird content. As an example, Substack is currently a place where you can find content that makes you think. The problem is, for most of the web-- what I think of as the 'popular web'--, that isn't the case.

The popular web mostly exists on the giant platforms (social and/or media), and takes one of two forms: content and conversation.

'Content' is what you find on the front page of YouTube, the average Instagram feed, or a high-schooler's TikTok account. In three (compound) words: short-form, personality-driven, and high-virality. Being on the popular web means being subject to constant bombardment by this type of content. It constantly demands our attention, it's mostly negative, and it generally contains very little informational value3. We're algorithmically pushed to numb ourselves under the deluge at all times, except for when we're zoning out to the advertisements that come for free.

Web content is just like off-web content, except for the fact that we can't seem to stop consuming it. This isn't really our fault. Unfortunately for us, thousands of the world's geniuses have been working tirelessly for years, hacking our psychology to optimize consumption. Given the current incentive structures and modi operandi of the web (see: ad-revenue driven), this isn't likely to change anytime soon. We all seem to have internalized this to some degree: everyone talks about the reality of their smartphone addiction, but in a tongue-in-cheek sort of way that implies they'll never do anything about it.

'Conversation' is the other part of the popular web. It mostly happens on Twitter, with other comment-based watering holes mimicking Twitter to greater or lesser degrees (see: comments sections of the big media platforms). I'll admit, I don't spend a lot of time on Twitter, so you'll have to accept my perspective as an informed outsider. Gratuitously, Twitter is 'postmodern purgatory limited to 240 characters'. Full-bore irony, skepticism and moral relativism of the most extreme variety, about everything, all the time.

I won't argue that there aren't good parts of Twitter. There is for sure some interesting discussion that happens there. I will argue those are very small parts of the whole.

How did this happen? What is it about web-based comment sections and toilet-tweeting that makes us so cynical, so short-sighted and reactionary4? Why does the web seem to bring out some of our worst qualities? The answer is obviously nuanced.

There's something to be said for the period the web (and its primary users) grew up in. The and 90s and early 2000s were the sunset years of postmodernism in popular media. Nihilism, cynicism, and heavy materialism permeated the childhoods of those that are now the web's regular denizens. The web also strips conversation of interpersonal physical cues (body language, for instance), and enforces a widespread pseudo-anonymity. These characteristics also contribute to the norms of conversation on the web, but they don't tell the whole story.

In his fantastic review of the book The Dawn of Everything, Eric Hoel outlines what I think is the most compelling version of the ills of social media. In it, he talks about the idea of the 'gossip trap', a theory for why it took humanity so long to develop large communities (i.e cities). According to Hoel, the web (in this case social media in particular) has hi-jacked something primal about the way humans participate in society. This default mode for human society is a prehistoric version of the high-school lunch table. It never exceeded the Dunbar number, and status reigned supreme. Leadership emerged from pure charisma and populism, and the out group is always vying to get back in to the inner circle through whatever gossipy-backstabbing was available.

In this framing, the reason conversation on the popular web sucks is because we reverted back to our default mode. We re-adopted a framework for conversation and that is quite literally uncivilized. We got beyond that default mode by inventing formal structures -- social contracts, institutions with authority, laws, government-- and from there we could operate our communities beyond the limitations of pure interpersonal relationships.

But in one generation of technological development, we've created and scaled the tools needed to re-awaken our Elder God. Social media is the perfect anti-serum to all the rigid foundations of society, built up over centuries. It allows us to fall back to our base mode of social organization, one that is now used daily by the vast majority of the developed world.

II.

So the web is trap, a place where low value content reigns, where economies exist for our attention, and where reactionary uber-gossip dominates the conversation. What does any of this have to do with cities?

Cities are the fundamental unit of human civilization. To borrow from biology, cities are like cells, the smallest stable form of human society. Cities form the base for bigger structures like nations and unions, but the civilization demands cities at a minimum. When we first emerged from the clutches of the gossip trap, we did so in the form of cities. Empires and expansive nations have been fluid throughout history, rising and falling, but cities have remained stable. We don't have the Roman Empire any more, but we still have Rome.

Cities are also the smallest form of community where relevant societal changes happens. Cities are big enough for changes to the society within to matter, but also small enough that those changes happen organically, bottom-up.

Let's use smoking indoors as an example (in the US, at least). Once upon a time, we considered smoking cigarettes a normal part of everyday life. Most people didn't think smoking was bad for you. People smoked inside. Cigarettes were ingrained in the default fabric of society. This is no longer the case, but the transition from 'everyone smokes inside' to 'nobody smokes inside' didn't happen in one fell swoop.

San Luis Obispo, California was the first city in the US (and possibly the world) to ban smoking indoors in 1990, and before then even talking about a place where you couldn't smoke inside was strange. San Luis Obispo was the first, but it was in many ways the primary domino, a foreshadowing of how smoking as a social norm would play out in America.

This is the future of the popular web as well. An understood detriment to society, and one that communities regulate out of necessity.

Right now the web exists as an unexamined default in the backdrop of modern society. We consume the content and take part in the conversation, but it's only more recently that we've started casting a critical eye on the web's pitfalls. Much like San Luis Obispo, I think we'll soon have a city in the US that starts implementing limitations on the use of the web. Will it start with giant Faraday cages, or draconian firewalls? Certainly not. It will probably start with 'web free Sundays' born out of a growing sense that we need to start limiting this thing somehow. And it'll grow from there.

Green Bank is a town in West Virginia that has extremely limited access to the internet, by law. For all intents and purposes, the modern web does not exist there. Green bank is currently an oddity, a tiny town with a unique constraint that makes having ubiquitous internet availability (and therefore web availability) impossible. It's against the law to try and use a cellphone to send a tweet, or watch an online video.

I see a future where Green Bank is much closer to the average American city. Sure we'll still have places where access to the unrestricted web is available, like we have places where you can smoke inside and bet on sports games and gamble money away on the hope of a hard six. We'll have those type of places for the web, but we'll all agree that there are good reasons for limitations to exist, that completely unrestricted access is a detriment to society.

III.

I'm well aware of the irony here. I wrote this for the people of the web and distributed it on a contemporary web platform. It would probably not exist in the world I'm describing. But the reality is, these corners of the web are not the web. Substack, and the few places on the web like it, do something special by creating the kinds of intellectual spaces that have historically driven humanity forward.

The best parts of the web are the book clubs, seminars, academic societies and dialectic saloons— dedicated places where intelligent individuals from all over the world can interact and express their thoughts, share their writing, spread their ideas. These gatherings of minds are what make the web a place worth spending time in. But it's not what most of the web’s users are doing here. The web is an amazing tool for connection and understanding. Just think about how much we can know about places we’ve never been, about people we'll never meet, about eras we cannot live in! We have the collected knowledge of humanity at our fingertips, and the ability to connect with anyone, anywhere. But that’s only a small fraction of what goes on here. We need more than the tiny havens we wave. We need a place where the default for conversation is something other than sniping, cancelling, and infighting. A place where the content we consume inspires us rather than numbs us.

Real, community, productive community that moves humanity forward can't exist on a foundation of hyper-efficient capitalism and 240 character comments. So unless we can figure out a different default, we'll need to start building more Green Banks.

Thanks to Evyn Tindle for reading drafts of this piece, and thanks to

for the inspiring prompt!This piece is actually a (really tardy) response to

's prompt "Dream up a utopian city", as part of her utopian essays/novel project over at .I'm trying to be very particular about using web versus internet here, though they are generally used interchangeably. I'm talking about the types of experiences the internet currently enables, think ad-centric platforms, social media, etc. (web), rather than the infrastructure that makes those experiences possible, like the HTTP protocol, the actual datacenters, etc. (internet).

That’s not true of the places on the web you tend to hang out in, of course. Just the rest of it.

An interesting attribute of both web content and conversation is that they're typically dominated by recency. This is something David Perell calls The Never Ending Now, essentially making the observation that the things we consume and participate in on the web are driven by recent news, events, trends, etc., usually as young as 24 hours old.

This is a very interesting essay. I certainly agree much of our web experiences are toxic or least a waste of time. And we need to figure out a way to help the internet to become a more positive force in our lives.

Yet the solution you present here seems far worse than our current reality.

Creating “sophisticated firewalls that separate the internal networks from the global web, a digital shield against the informational wasteland beyond” is essentially what is happening now in some authoritarian counties.

During popular uprisings cutting off access to the web completely is seen as a means to reestablish control.

On a day to day basis it’s also a good way to shield the local population from outside influences that might prompt them to question their current situation and leaders. China among others has made great strides in limiting access to outside influences and transforming the internet into a tool for monitoring and social control. What’s your “social credit” rating?

Today everyone -- including many among the overwhelming majority of the population who never use it -- talk about what a cesspool Twitter is. Every one of them has make a personal decision about whether they use it or not.

As a result Twitter has a pretty small and declining user base compared to the other platforms. All the big social media platforms are in decline as young people in particular flee to more relevant and friendly sites.

No Faraday shields needed.

This kind of personal decision making doesn’t seem to play a role in so many future utopias.

Much like the one envisioned in this essay, someone -- a future Ayatollah -- would decide that access to the outside web is bad for public morals. Authoritarianism is always it seems a matter of public good and imposing limits on freedom and punishing those who don’t agree are hallmarks of the authoritarian state. Even the most progressive people become little fascists when presented with the chance to ban something they don’t like.

So I can easily imagine a future in which the “radio quiet zone” of Green Bank has extended its reach throughout the country. Everywhere it’s “against the law to try and use a cellphone to send a tweet, or watch an online video.”

You could also see a surging need for an army of “radio policeman" like those in Green Bank to ensure no one is polluting themselves or others with Twitter.

By the way, one reason people move to Green Bank is because they believe themselves to be suffering from “electromagnetic hypersensitivity.” Some already talk about how toxic the internet has become and it use could be seen as a public health issue I suppose -- like smoking.

Somehow that doesn’t sound like the kind of utopia in which personal freedom plays much of a role. And if it doesn’t then someone must swoop down from a great height and make decisions for everyone else. Is that a utopia?

Interesting. So are you saying we keep the internet, but effectively eliminate Twitter (and the bad web) in favor of Substack (and the good web)?